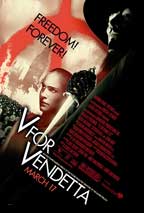

V for Vendetta -- a Milestone (2006)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on April 10, 2006 @ FYLMZ.com.

V for Vendetta is a milestone. Maybe not a big marker, but a milestone nonetheless. It is anti-establishment redux.

Three years ago V for Vendetta would never have been released. it's about a man who blows up government buildings. But in the last three years the landscape has changed; skepticism -- which was exiled from the public scene -- has begun a slow recovery.

This is not to say that the voices of skepticism ring loud and clear. They usually don't. Too often skeptic Bill Maher sounds more like Red Skelton -- snickering and preening -- than Mort Sahl. And the fallacious "fair and balanced" has trumped skepticism again and again.

But V for Vendetta reopens a paved-over path. And the fact that it is part of popular culture and has had a successful run so far -- opening number one at the box office -- suggests that something new perhaps is afoot.

V for Vendetta was adapted by the Wachowski Brothers from the graphic novel by Alan Moore and illustrated by David Lloyd. The Wachowskis are most known for writing and directing The Matrix trilogy. This time out they only wrote the screenplay; they assigned Jim McTeigue to direct. McTeigue was first assistant director on the three Matrix movies.

Moore has taken his name off the movie because the Comics company that published his grapic novel never gave him ownership of V for Vendetta as he was assured they would. Unfortunately the novel never went out of print which was the stipulatrion for ownership reverting to him. It seems the rancorous Moore may have cut off V's nose to spite his face.

The Wachowskis have done other surgery. The change that the Wachowskis have made that most offends Moore's devotees is that they have changed Moore's anarchism to their own liberalism. Moore is a self-described anarchist; the Wachowskis are not. They have shifted the major conflict from the book's fascist government versus an anarchist into the movie's fascism versus liberalism. Anarchy is not big box office.

Moore's V for Vendetta occurs in 1997 and is the story of a man who is out to destroy the Fascist order that has been imposed on England. This protagonist calls himself V and wears a porcelain Guy Fawkes mask. Guy Fawkes was the radical who tried unsuccessfully to blow up the House of Lords in 1605.

Moore told GIANT magazine, "They're making too much of this Guy Fawkes thing. Guy Fawkes was not a freedom fighter; he was a religious fanatic." For Moore, V is not a hero; he is "a force." Moore declares, "... I was just using Guy Fawkes as a symbol, without really any reference to the historical Guy Fawkes."

But the Wachowskis change V into a freedom fighter. The modern V (masked but not constrained Hugo Weaving), with the help of a young woman (the inimitably appealing Natalie Portman), tries to accomplish the task at which Guy Fawkes failed, and take it further.

The Wachowskis also update the plot from 1997 to around 2020.

Another major change that they make is that they don't blow up parliament at the beginning as happens in the graphic novel. Instead the Wachowskis have the Old Bailey explode at the beginning. This changes the context.

The Wachowskis have added V's love of the movie The Count of Monte Cristo with Robert Donat, which informs V with swashbuckling romanticism. To keep it pristinely romantic, they don't have V and the young woman have sex as they do in the graphic novel.

And, if the Wachowskis are involved, you can be sure religious allegory is just around the bend. Moore has one character named Adam, another named Evey, and a redemptive figure who comes out of an ordeal -- the Wachowskis have him stretch out his arms. This had to be absolutely irresistible for the Brothers.

For all their transformations, they come up with a movie that is entertaining and may pique our sensibilities.

Indeed the movie V for Vendetta is anti-Establishment -- an almost forgotten concept from the 1960s-1970s. V for Vendetta is refreshing deja vu for those of us brought up on The Graduate, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, All the President's Men, Nashville, and all the films of alienation, rules broken, and systems challenged.

Times and attitudes change. When I was teaching college students in the 1980s, I once asked who among them was anti-Establishment. Not a single person in the class was.

When I showed The Graduate -- which had once occasioned great applause -- at the end as Ben and Elaine fled on a bus, my students asked. "Where are their things?"

I doubt if audiences seeing V for Vendetta will ask, "Where are their things?"

Given the potential rebirth of skepticism, they may ask other questions.