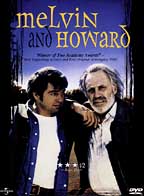

Melvin and Howard (1980)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on July 6, 2010 @ tonymacklin.net.

The most engaging portrayal of Howard Hughes on film is not by Howard Hughes -- it's by Jason Robards, Jr. in Melvin and Howard (1980). As Las Vegas' most mythic figure, Robards delivers a memorable, powerhouse performance as the aging icon out on the loose. He's the lion in winter in the desert.

In director Jonathan Demme's brilliant film, Hughes only appears at the beginning and at the end as a coda. But what a coda!

Demme tells the story based on some actuality of how Melvin Dumarr (Paul Le Mat) and Howard Hughes might have met. Later after Hughes' death a will -- actual or concocted -- named Melvin as a beneficiary of $156 million. This resulted in a firestorm of controversy and eventual court action which denied Melvin his inheritance.

Demme focuses on the life of blue collar dreamer and misfit Melvin Dumarr from the time he meets Hughes to the court case that rejected him. It's a peripatetic journey through the hopes and tribulations of blue collar America. It's the cockeyed American Dream, which crashes into red, white, and blue smithereens.

Though Robards only appears at the beginning and end of the movie, he is wonderfully memorable as Las Vegas' most mythic figure.

The movie opens with a shot of an expanse of water rippling in the desert like an oasis. It's the desert outside Tonopah, Nevada.

We hear sound -- a steady buzz. In the distance we see a speck. It comes into view. It's an old man on a motorcycle speeding across the desert. He's a grizzled wraith -- a goggled satyr -- yelling and laughing maniacally. He's in mad flight. It's the sound of freedom.

The reckless ride ends with loss of control and a crash, which leaves the daredevil in a motionless heap. It could be a metaphor -- in a movie of metaphors.

The scene then shifts to night and Melvin driving his truck down the deserted highway. He pulls his truck to the side of the road and gets out to relieve himself; when he gets back in his truck and starts to pull away, he sees something.

He gets out of the truck and goes to the inert body of Howard, who is a ghostly image with wild hair. Melvin helps him to his truck. There's the sound of a coyote in the distance. Melvin and Howard is a symphony of sounds. When Howard says to Melvin, "I'm Howard Hughes," thunder crashes.

Sitting in the truck Howard gives the ebullient Melvin looks of wary diffidence and disdain. They are priceless.

Melvin says he'll take the old stranger to a doctor.

"No doctors," Howard rasps.

Melvin tells that he works in a magnesium plant -- one of many blue collar jobs he's had. He's a dreamer. He's full of ideas. He has written a Christmas song, "Santa's Souped-Up Sleigh," which he gets the reluctant Howard to sing with him.

Melvin ultimately gets Howard to choose a song to sing. Tentatively, hesitantly, softly, Howard sings "Bye, Bye, Blackbird."

The poetic scene becomes even more evocative when it starts raining. Howard rolls down the window on his side, and breathes the air.

"Greasewood," he murmurs.

Melvin rolls down his window. "Sage," he says.

"Nothing like the smell of the desert after the rain," Howard says.

"Greasewood and sage," says Melvin.

The scene is a poem, two odd fellows relating in the natural world.

They drive into not-so-natural Las Vegas. The names Sammy [Sammy Davis, Jr.] and Carmen McCrae are on the marquee outside Caesar's Palace. Bob Newhart and Vicki Carr are on another marquee down the strip. It's another world.

Melvin drops off Howard, whom he doubts is Howard Hughes, in the back of a hotel. He gives him a quarter and drives away.

Howard walks toward the entrance at the back, smiles, and pitches away the coin.

As Melvin arrives home there's a country song about "red, white, and blue" on the soundtrack. His trailer is near a rusted, junked truck. Melvin climbs into bed with his sleeping wife Lynda, awakens her, and they embrace. (Mary Steenburgen won the Best Supporting Actress Oscar for her performance as Lynda, and Bo Goldman also won the Oscar for his wonderful Original Screenplay). In the morning Lynda gets out of bed leaving Melvin asleep. She's a vision of fickleness in red, white, and blue. In red shirt and blue jeans, she watches through the bedroom blinds as Melvin's cycle is repossessed. In the next scene she, wearing a blue dress with daughter Darcy in tow, leaves home in a truck driven by a man in a cowboy hat.

Later outside a motel she is left beaten by the cowboy.

Demme is perhaps the director who most uses colors, costumes, and mise-en-scene to emphasize that his movies are statements about American values and sensibilities, e.g., in his The Silence of the Lambs (1991), a serial killer was called Buffalo Bill, and American flags, and red, white, and blue dominated.

Flags and patriotic colors abound in Melvin and Howard. Sometimes they're obvious, sometimes they're sly. Production designer Toby Rafelson, at one time the wife of director Bob Rafelson also a social critic, serves Demme well.

In the next scene when Lynda puts Darcy on the bus from Reno to Las Vegas back to Melvin, the bus is white and blue. Demme adds a red apple which Lynda gives Darcy.

The lockers in the bus terminal all are red white, and blue. American staples are red, white, and blue -- e.g., Pepsi machines and a Standard Gas station sign.

Demme often adds red to the other two colors -- a red suitcase in a club, a character drinking red wine while watching tv, a red shirt in court. There's hardly a sequence without the three symbolic colors. The background speaks America.

Demme's choice of music is piquant. Melvin chooses "Hawaiian War Chant" to accompany his remarriage to Lynda in a wedding chapel in Las Vegas. It's catchy kitsch. Red, white, and blue bathe the ceremony. Lynda, who is pregnant, is all in blue. Melvin buys a blue veil, although they couldn't afford the $5 it costs. Darcy is in red, white, and blue -- mostly red.

Demme plays the scene for broad humor. After they are married, Melvin and Lynda are hired to be witnesses at the wedding chapel. And there's montage of enthusiastically kissing strangers. It's silly and amusing.

The image of old Las Vegas: a wedding on the strip -- and on the cheap. It exhausts the Dumarrs' meager finances.

Demme shows the American Dream turned tacky and populist. When Lynda appears on a television game show Easy Street her "talent" is tap dancing. She tap dances to a recording of the Rolling Stones'

"Satisfaction." America tap dances on classic popular music. Two worlds are obliterated in one.

Easy Street has a glib -- somewhat smarmy -- host who leers at female contestants and speaks platitudes. Melvin, sitting next to an American Indian in the audience, cheers Lynda and the door that offer prizes. By audience applause, always a shaky barometer, Lynda wins the competition and picks doors to fortune. Or at least material accumulation.

After Lynda wins on Easy Street, Melvin makes a bevy of affluent purchases. He drives up to their new house in a red car with a blue license plate, pulling a big, white boat.

Lynda declares, "Melvin, you're a loser."

"That stuff's an investment," Melvin responds.

"I used to dream of being a French interpreter," Lynda says.

"You don't speak French," Melvin says.

"I told you it was a dream," she says and she leaves him for good.

Dreams are illusions. but Melvin fiercely clings to them. Absurdity can be funny, withering, or poignant. In Demme's vision, it's all three.

Like Lynda on Easy Street, Melvin has his road to success. He drives a truck delivering milk and affection door to door.

He lusts to become "Milkman of the Month," an "honor" which he achieves, but it's lost it value because the company keeps dunning his salary.

The Dream is spiritual -- Success is not.

Eventually Melvin goes to Utah with Bonnie (Pamela Reed), a young woman who works at the dairy, who has inherited a gas station in Utah.

On tv they see the announcement that Howard Hughes has died. Later a very well-dressed man comes to the office of the gas station to buy cigarettes.

"Nowadays they want long ones and filters," Melvin says about the changing times.

After the man is driven away, Melvin finds an envelope the man left on his desk. It contains a will in which Hughes made Melvin a beneficiary of $156 million. Melvin, Bonnie, and Darcy go wild.

Melvin takes the envelope to Mormon Plaza in Salt Lake City and puts it in a pile of mail in an attorney's office. It's discovered, announced publicly, and hordes descend on the gas station. It's a media zoo.

At one point there's a shot of Melvin hiding behind a tree watching the frenzy. Nature protects.

Melvin goes to Las Vegas' Clark County Courthouse, where religion and "justice" prevail. Melvin loses

But like for many dreamers, the journey is more important than the achievement. Melvin admits that he knew all along that he wouldn't get the money -- the powers-that-be wouldn't let him.

But he did get fulfillment -- not just satisfaction.

"That's all right," Melvin says. "Howard Hughes sang Melvin Dumarr's song. That's what happened. He sang it. He was funny. Yeah, he sang it."

The last sequence returns to Howard and Melvin in the truck. Melvin is napping in the passenger seat, and Howard is driving through the night.

Howard croons, "Bye, Bye, Blackbird," as they drive on.

Melvin and Howard is an anthem to the human spirit.

Heading for Las Vegas.