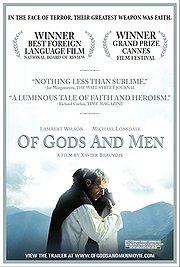

Of Gods and Men (2010)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on August 16, 2011 @ tonymacklin.net.

Of Gods and Men is a tribute to intelligent faith.

In a world in which faith and ignorance are often yoked together, Of Gods and Men lifts faith from just the throbbing heart to the thinking mind as well.

In a world in which reading one book makes a person superior to those who have read thousands, intellectual knowledge may be irrelevant. But Gods and Men brings back its relevance.

Based on actual events, Of Gods and Men is a French film that transcends some of the controversy -- political and factual -- and instead focuses strongly on human nature under duress struggling to be its best.

Of Gods and Men is the story of eight monks (a ninth returns near the end) at a Cistercian monastery in the mountains of Algeria in the 1990s. They are threatened by severe danger.

The world around them is in brutal chaos. Islamic fundamentalists are on a bloody rampage -- killing unsubmissive women, Croatian workers, and villagers. And in return the army is violent. It's a cauldron of hate and devastation. Both sides are merciless.

Being martyrs is not the ideal of the monks. They want to live -- some desperately. But sometimes allegiance to faith demands ultimate mortal sacrifice.

Christian (Lambert Wilson), who has been chosen prior, tries to lead monks who question him. They have to decide whether to stay or leave. It is not an easy decision. The monks are old men who sometimes think they're fecund, other times, fallow. The outside world is encroaching on their simple lives.

Christian reads both the bible and the Quran as sources of knowledge and understanding.

The monks serve the Algerian community and attend their families' cultural activities. They respect the others' faith and don't try to convert them.

Every day aged Brother Luc (Michael Lonsdale) as doctor tends to the ailments of the community -- there's a waiting area constantly filled with villagers waiting for treatment from him.

A female villager says to a monk, "We're the birds. You're the branch." But the branch is fragile and snow-laden.

One night as the monks are celebrating Christmas, Christian is faced with the terrorist Ali (Farid Larbi) who demands medicine for his wounded men. Christian quietly refuses, saying the medicine is for the villagers.

Ali and his men leave. It is a scene in which the two men momentarily communicate. Of course, it is just a moment that abruptly will pass.

But such moments present a human face amidst horror.

Lambert Wilson is compelling as the thoughtful prior. Michael Lonsdale gives his character Luc the weight of vast humanity. When Luc is cursed by another monk, he says, "He's just tired." Luc is a paragon of understanding.

Director Xavier Beauvois -- from a script by Etienne Comar -- treats his subject with quiet, somber eloquence. He is both subtle and obvious; he creates immediacy and foreboding.

One scene in which he is obvious is the crucial scene of incarnation in which the monks sit around a table drinking red wine and listening to the rapturous music of Tchaikovsky's Grand Theme from Swan Lake. It seems a heavy, obvious choice, but it works. It swells the spirits of the monks -- and the viewers, if they let it.

Caroline Champetier's cinematography is evocative. In one scene -- which seems an allusion to one interpretation of what actually happened -- the monks garbed in white sing in a chapel as outside a noisy helicopter with a machine gun sticking out hovers above them.

The final images Of Gods and Men have a power and beauty. They are mysterious and symbolic.

Like faith, they resonate.