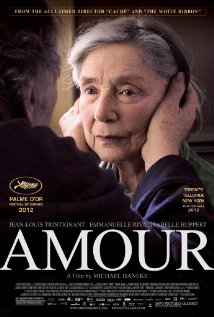

Amour (2012)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on January 21, 2013 @ tonymacklin.net.

Amour, on its first viewing, is depressing.

It's still depressing on its second and third viewing. If that's true, then why should one watch it?

A viewer may want to watch Amour, because it is a work of art. If one is willing - and able - to participate in his film, Austrian director/writer Michael Haneke provides the viewer with the keys to his style and vision. We can unlock entry into a personal view of the human condition. It's also uniquely universal.

In a way, Amour is brutal voyeurism. It's a film about the deterioration of a woman in her eighties and her husband's attempts to care for her as she fades into ugly oblivion.

Anne (Emmanuelle Riva) and Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) take part in a slow dance of death, as she steadily declines. They dodder and shuffle together in awkward embraces. But, despite the loss and despair, it's an experience that is ultimately human. Death only comes after life.

Amour is full of memories - of flowers, movies, music, stories, and connections.

The entire film, except for the couple's attendance at a recital, takes place in the expansive apartment of Georges and Anne.

People enter - authorities break in at the beginning of the film, the concierge and his wife tend and shop for the couple, the daughter Eva (Isabelle Huppert) and her husband visit, two men assist Anne in her wheelchair when she returns from the hospital, nurses attend, and a former student, now accomplished, plays the piano for Anne.

But despite its random visitors, the apartment remains an isolated and alien place. It's mostly as deserted as an island. The bookshelves are full of books, and the couple still reads, but often the rooms are dim and empty. Life is waning.

The present is isolating. Georges tells Eva that no one can understand what he is experiencing. Eva is living beyond the existence of her parents. Her concerns are about property and generic solutions that effect her.

Haneke creates a setting that is a major character. Amour is a film of doorways, doors that are closed and opened - locked and broken into -, windows open and shut, rooms empty and still. The doorways seem like passageways of life. Various and compartmentalized.

Darkness prevails. When a lighted lampshade is red, it has added visual impact, because light often is absent.

There is a wealth of symbolic images - the empty wheelchair beyond the middle of Anne's bed, like a silent witness. A pigeon enters the apartment window - twice. It is more alive than Anne. Georges writes that he let it go, "This was the second time. But I let it go again." The irony is stark.

Haneke is especially fortunate to have such marvellous leading actors as Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva, with their fabled history.

Haneke cleverly utilizes details with elusive meaning. As Anne looks through a photo album, we see a photo of Trintignant sitting opposite Roy Scheider. The two actors appeared together playing hit men in Los Angeles in the film The Outside Man (1972). It's a title that reverberates.

While looking at the album, Anne says, "It's beautiful." Georges asks, "What?" Anne answers, "Life."

Earlier talking about his "image," Anne said, "You're a monster sometimes. But very kind."

In Amour, life itself is kind but is monstrous. Human action is monstrous but is kind.

Haneke uses sound to great advantage. Sounds prevail - running water from a spigot, a spoon clattering against a bowl, loud piano playing, a doorbell ringing twice, heavy breathing in the dark, feet scraping haltingly on a floor.

Haneke shows us life as motionless, almost frozen images - the audience sitting at a recital facing the camera, Anne sitting staring into space, and empty room after empty room.

Dualities are in abundance. Haneke is an ironist. Amour deserves multiple viewings. It seems an apt subject for probing interpretation.

Although much of its concentration is on death, Amour stays hauntingly alive after its characters are gone.

Like lasting art.