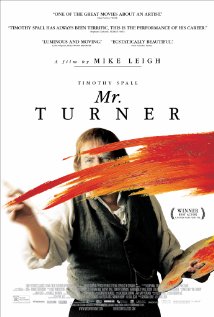

Mr. Turner (2014)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on February 10, 2015 @ tonymacklin.net.

Mr. Turner, for better or worse, is a film that stays with you.

One may look at his watch during the 150-minute viewing which is an ordeal, but days later the film still has impact.

Mr. Turner is a portrait in light and dark. It's a portrait of an artist and man. It's a portrait in strokes and blotches.

Writer/director Mike Leigh evocatively captures both the immortality and mortality of J.M.W. Turner - the fabled 19th-century English painter.

But the film is not about how one evolves as an artist. It begins when Turner (born in 1775) was in middle-age and had already achieved fame and status. The movie is about the last 25 years of the painter's life. A surprise is how little painting Turner does in the lengthy film. Turner spends much more time looking, experiencing, and considering - not painting. Where did all those paintings come from?

Times change and reputations fluctuate, and the 72-year old Leigh is aware of that, but he seems to be after something else. What is the point of the movie?

Mr. Turner is about a man accomplished in the art of painting, who is not accomplished in the art of living. Despite that, he often thrives. Sensitivity does not get in his way.

Timothy Spall makes an arresting Turner. Turner wanders, trudges, lumbers, and plods across the screen. His above-average vocabulary is constantly accompanied by a cacophony of guttural sounds - growls, wheezes, and grunts.

Turner is part artisan, part animal. Huffing and puffing.

He's often boorish and callous. At times he can be cruelly inattentive, but on occasion he can be sensitive. He often scowls, but can guffaw. He can be gregarious, but searches for solitude. He has different facets, but is not an enigma.

Turner is a flawed, gifted human being.

Mike Leigh transports us to another world. One strategic move that Leigh makes is that he never identifies time or place on the screen. Most films do, but Leigh dismisses the convention. Without it, the scenes become more immediate.

It's immediate but it's distant. We see a man carving the cheek of a hog's head on a table. We witness the Scottish polymath Mary Somerville (Lesley Manville) experiment with a prism producing violet light. Turner and his landlady/lover Sophia Booth (Marion Baily) go before a new invention, the camera.

The seaside town of Margate, where Turner visits the shore and Sophia, is changing. Turner's housekeeper Hannah Danby (Dorothy Atkinson) adores Turner, who ignores her except for brushes, wine, and occasional impersonal sex. As time goes on and her life is ravaged, her face is increasing marred by a disfiguring skin condition

The artist community and the upper class are superficial and often unpleasant.

One problem for me is that I wouldn't want to spend ten minutes with these people, but I have to spend 2 1/2 hours with them on the screen. Turner spent a lifetime.

Leigh's screenplay is effective. At least language has a flourish. The characters use words such as "peruse," "cogitate," "execrable," and "repaste."

Leigh makes one contrived intrusion in the characterization of John Ruskin (Joshua McGuire), who was a foremost art critic. Leigh turns him into a loquacious ninny. There is no way this twit could be a major art critic. I guess he could be a movie reviewer.

The ambience of the film is a wonderland. Cinematographer Dick Pope, production designer Suzie Davies, and costume designer Jacqueline Durran cast spells.

Leigh employs them to aid him in exposing the human condition.

In the final images of Mr. Turner, two of the women are juxtaposed. Sophia Booth is cleaning the window panes of her front door. She seems content.

The other image is of the house maid Hannah in a darkened room with paintings. She is bent over toward them.

The artist - and man - has left one woman busy and cheerful; he's left the other woman broken and trapped.

One is in light; the other isn't.

Such is the legacy of Turner.

Such is the human condition.