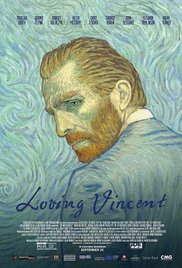

Loving Vincent (2017)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on October 21, 2017 @ tonymacklin.net.

Some films transport you to a different time, place, and atmosphere. They take you on journeys that you think are familiar, but then they surprise you. A few become tantalizing.

The hand-painted, animated Loving Vincent is such a film.

A lot of people know something about Vincent van Gogh. He was a painter who cut off part of his ear. He was a tormented soul.

Loving Vincent takes us beyond the myth. It is an elegy steeped in mortality.

Partially funded by the Polish Film Institute and a campaign by Kickstarter, Loving Vincent is a film that pokes and prods at the enigmatic character of the Dutch artist. And it does it in masterly style.

The plot is simple - in 1891 the son of a postmaster goes on an odyssey to deliver the last letter Vincent wrote to his brother Theo before Vincent's death. But Theo also has died, so the letter carrier searches for someone to give the letter. His journey takes him to Auvers-sur-Oise, where both Vincent and Theo died.

In his dogged search, he gains conflicting gossip and information from those who knew Vincent the man. Vincent was a "nutcase," "polite and kind," a "genius," a "rough and awkward man," "an ill man." And in Vincent's own words, people thought he was "a nobody, a nonentity, an unpleasant person." He was a human hodgepodge.

It always has struck me as a withering irony that Vincent van Gogh never knew what his legacy was to become. During his life, he sold only one painting. he died in utter futility, melancholia, and alienation. He never proved himself to himself. His mortality robbed him of his own transcendence.

Twice in my life, I experienced the power of great art first-hand. I saw Michelangelo's Pieta, bathed in blue light, at the Vatican Pavilion, at the World's Fair in New York. I stood in a long line to experience it.

But my most personal experience with great art was when I sat alone with my wife Judy on a bench in a dark room at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in front of van Gogh's Sunflowers on the wall. At the time we were the only people in the room with the precious object. [There are five different van Gogh paintings of Sunflowers at international sites.]

Loving Vincent is an odd, sometimes quaint, enticing film. At times it's beguiling; at other times it's ordinary. But it's adventurous.

Directed and written by Dorota Kobiela and her husband Hugh Welchman (Jacek Dehnel also was a writer), Loving Vincent is an elaborate enterprise.

Visually it's experimental. More than 100 painters hand-painted the images. Because it's such a gathering of painters, they may not all be stellar, but they get the job done.

The black and white photography adds clarity and resonance. When the photography changes, it becomes shimmering pools of color in homage to van Gogh.

The directors realize the value of sound. In Loving Vincent, sound abounds: the splash of coffee into a cup, the distant barking of an animal, the slam of a door, the thwack of a punch, the caw of a crow, birds chirping, crickets murmuring.

The actors' images and voices are apt. Saoirse Ronan is Marguerite Gachet, the appealing daughter of Dr. Gachet (Jerome Flynn). Chris O'Dowd is the postmaster, and Douglas Booth is his son who goes on the fateful travel. Robert Gulaczyk is Vincent. But the actors fade into the affecting imagery.

The screenplay is serviceable. It offers multiple theories on Vincent's death, and it seems to settle on the traditional one.

Loving Vincent is manipulative, but in general it's good manipulation.

The credit sequence at the end is accompanied by British singer Lianne La Havas' beautiful rendition of Don McLean's Starry Starry Night. It's an appropriate ballad of spirituality.

The modern world usually chooses commerce over creativity. The van Gogh painting of Sunflowers that I personally saw is valued at $300 million. That figure defines van Gogh to many investors.

But the stars are worth more. They're not for sale.