Man in the Dark: On David Fincher's Zodiac

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on May 1, 2007 @ Bright Lights Film Journal.

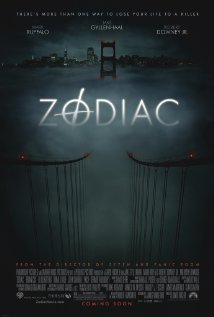

Zodiac probably is more of a critic's picture than an audience picture.

Since it is about an actual serial killer — Zodiac, who terrorized Northern California from 1968 through the early 1970s — it should appeal to the masses. But instead of being essentially about the thrills and chills of killing, it is more about investigative processes. Two hours and 40 minutes of grueling investigative processes.

Zodiac should intrigue critics because it is about themes instead of action, verisimilitude instead of crudity, and detail instead of cliché. It's a deceptively rich film.

Directed by masterly David Fincher, it takes its own time, pace, and downbeat style. Cean Chaffin, Fincher's longtime producer, once told me that Fincher's cut of Se7en (1995) ended with the uncovering of the head, but the studio wanted a different ending. A speech — Morgan Freeman quoting Hemingway — was added. It provided synthetic uplift.

Fincher was told if the screening of the studio version wasn't better received than Fincher's, they would go with Fincher's preference. The reaction to both was the same, but the studio went with their version.

With Zodiac, it seems Fincher has more clout, and the movie is his.

Zodiac begins on July 4, 1969, on the outskirts of Vallejo, California, when Michael Renault Mageau, 19, and Darlene Elizabeth Ferrin, 22, are shot in their car while parked in an isolated area. She dies; he survives.

Days later, letters are delivered to three newspapers — the San Francisco Chronicle, the San Francisco Examiner, and the Vallejo Times-Herald — each accompanied by part of a cryptogram. The letters are from someone who calls himself Zodiac, and they contain information that only the killer of the girl in Vallejo would know.

Zodiac also admits to committing two murders that occurred the previous December. He says the cryptogram will identify him, and he threatens a rampage of killings if the papers don't publish his material on the front page.

In the film we see the letter delivered to the Chronicle, the debate about it by the newspaper's editorial board and publisher, and the decision to publish it — although not on the front page.

But Zodiac coverage soon vaults to page one. And a legend is created out of fear and fascination. Zodiac and the media feed off each other. And so, modern journalism was born. The Zodiac Network was the precursor of Fox News. One can almost smell Nancy Grace interviewing the victims and blaming them for surviving.

Zodiac can be divided easily into three parts — the killings, the investigations by law enforcement and the media, and years later the emotional and psychological cost on those who still are haunted by questions about the whereabouts and identity of Zodiac.

Director David Fincher has assembled a first-rate cast. Jake Gyllenhaal portrays Robert Graysmith, the young editorial cartoonist who loved puzzles and became involved and eventually obsessed with the identity of Zodiac. The movie is based on Graysmith's two books about the killer.

Robert Downey, Jr. — swathed in scarves and goatee — plays the flamboyant Chronicle crime reporter, Paul Avery. Avery becomes battered by drugs and alcohol and the mystery and danger of Zodiac, who issues him a personal threat.

The movie also focuses on two San Francisco police detectives who become entranced by the spell of Zodiac. Anthony Edwards excels as the quiet William Anderson, and Mark Ruffalo gives his best performance since You Can Count on Me (1999) as the idiosyncratic, vain David Toschi. Toschi supposedly was the model for both Dirty Harry Callahan and Bullitt.

Director Fincher tries to recreate many of the actual details of his real-life characters. He has Ruffalo appear in a bowtie, which Toschi wore. Fincher often gets the real details, but ironically they sometimes lack meaning. He has Ruffalo eat animal crackers; Toschi had a penchant for them. But it winds up being a detail that seems more contrived than real. He has a movie poster of Illegal with Edward G. Robinson on Graysmith's wall. Again, it seems a mere detail.

Other standouts in the cast are Chloe Sevigny as Graysmith's girlfriend and wife, and Philip Baker Hall as a handwriting expert. Brian Cox as attorney Melvin Belli chews what scenery is left by Robert Downey, Jr.

Charles Fleischer is ominous in a basement scene that seems to come from The Silence of the Lambs.

Since Zodiac is a David Fincher film, it contains his major emphases on fear and games. Fincher loves competition — brutal games, such as in Se7en, Fight Club (1999), and Panic Room (2002) and slick games, such as in The Game (1997). Zodiac creates a brutal, slick game.

Fincher returns us to a different world — the late 1960s and early 1970s. It had many of the foibles and absurdities that exist today, but it lacked some of the contemporary tools that make our absurdity easier today.

To make a phone call, Graysmith had to go out to a phone booth in the rain. PONG — the first Atari video game — was on a TV. Many of the police offices didn't seem to have rudimentary electronic equipment so they could communicate.

Another concept that may seem passé is the police's adherence to due process of law. Toschi attends a screening of Dirty Harry and walks out bothered by what he sees on the screen. An ancient concept has been trampled. It's scenes like this that seem connected to the present. Movies influence us.

The script by James Vanderbilt is layered. It is full of dualities — one surviving, one not surviving. In the murder at Vallejo, the girl dies, the man survives. In the murder at Lake Berryessa, the girl dies, the man survives. The cop partners split. Anderson quits; Toschi keeps going. The press partners split. Avery goes off to his houseboat for drink and drugs, and Graysmith presses on.

Graysmith is married twice. In his first marriage he had two children; one is with him. In his second marriage, he has two more children.

Pairs are everywhere. Anderson celebrates his birthday twice; Zodiac uses double postage stamps; there are two men at the Vallejo Recreation Center telling about the prime suspect. There are two blue jackets in the suspect's closet, and he has two .22-caliber guns.

The production design by Donald Graham Burt is ultimately important. He recreates the look of the time — often a drab and dingy world. Burt creates the dullness of normalcy. The prime suspect Arthur Leigh Allen (John Carroll Lynch) is a child molester, but is very ordinary looking.

But Burt uses color to great effect. He creates a world of orange and taupe. Amber — warning — is the color that dominates. Graysmith wears orange shirts and drives an orange VW Rabbit, and the Hall of Justice is yellowish. The Chronicle newsroom has yellow pillars and dull walls under the glare of florescent lights. Near the end, one of the victims sits in an orange chair and identifies a picture of Zodiac.

Zodiac is about the game that a serial killer plays with the law, media, and society. He changes our culture. He creates a world of fear and confusion. Evidence is lost, misinterpreted, and ignored. Trivia, false leads, errors, and conundrums abound. Futility and failure endure.

Out of cultural clutter and mayhem, myth prevails. It's the human condition, and a warning for our time.