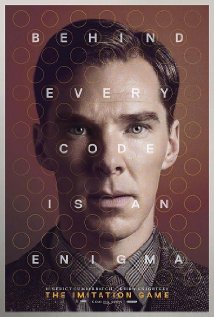

The Imitation Game (2014)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on November 27, 2014 @ tonymacklin.net.

2014 may go down as the year the music kidnapped the movies.

Film after film this year is awash in music that tries to lead the audience by their ears.

It's as though directors - maybe the producers - don't trust their actors and their writers. They seem to count less and less on the spoken word. Superb performances are cheapened by sound. Not the sound of voices. Not the sound of dialogue. Not the sound of language.

But the sound of incessant music.

Going to many movies today is like a two-hour elevator ride up and down with the music crowding in on every floor. Stereophonic music has become music on steroids.

Interstellar went through the roof with Hans Zimmer's relentless music. In The Theory of Everything, composer Johann Johannsson overwhelms Stephen Hawking.

One of the latest examples of music gone amok is The Imitation Game. This time British mathematician/cryptanalyst Alan Turing (Benedict Cumberbatch) is soaked in music. All the other characters are splattered.

The Imitation Game, with a screenplay by Graham Moore based on a book by Andrew Hedges, is the story of how Turing led the breaking of the German Enigma code in World War II. Benedict Cumberbatch plays the actual person.

The Nazis are not Cumberbatch's main enemy - composer Alexandre Desplat is.

Almost every time a character opens his or her mouth to speak, the music floods in. Conversation after conversation is bathed in music. The few conversations that are allowed to be spoken without music are effective.

Like The Theory of Everything, The Imitation Game has gifted, memorable performances, but it doesn't trust its audience.

Of course, Cumberbatch is sterling as the brilliant but socially-inept inventor. But it's hard to get the image of The Big Bang Theory's Sheldon Cooper out of one's mind, until about midway through the film. Also the music acts like the laugh track in The Big Bang Theory - "audience, you're not smart enough to understand the dialogue, so we'll tell you when to laugh."

The music in The Imitation Game tells you when to sigh. One rigged scene is when the brother of one of the cryptologists is on a ship the group knows is going to be sunk. The idea that they have awareness of fates does not have to be bicycled-pumped with the helium of sentimentality. A better film wouldn't have stooped to that.

One rare moment of subtlety is when the machine works. Turing and Alexander don't hug or shake hands; they simply share a look. The film needs more of those moments.

The cast deserves better. Besides the inestimable Cumberbatch, Keira Knightly delivers a bright and sensitive performance as the woman to whom Turing relates.

Underrated actor Mathew Goode provides his patented likeable humanity as Hugh Alexander, the chess champion who first leads the group. Charles Dance is forbidding as the Navy Commander. And Mark Strong is properly cool and mysterious as the MI6 agent Stewart Menzies.

The Imitation Game is directed by Morten Tyldum - of the Tweedledee family of directors. The man loves his music. But the swell of music is not so swell. He's a hop, skip, and jump director switching from era to era.

The fine actors deserve more silent room to work.

The Imitation Game doesn't have to be a replica of its title. It doesn't have to be imitation.

But the music makes it so.

The Imitation Game is a two-hour elevator ride. Cumberbatch, et al, make it pleasantly bearable, but it could be so much more.