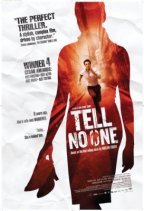

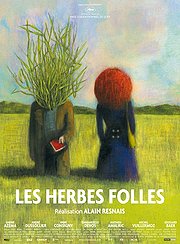

Wild Grass (2010)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on August 29, 2010 @ tonymacklin.net.

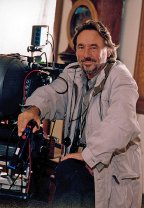

In Wild Grass 87-year old director Alain Resnais sows his wild oatmeal.

Born in 1922 (now 88), Resnais was a paragon of the French New Wave (La Nouvelle Vague) in the late 1950s and 1960s.

His latest film Wild Grass is completely open to interpretation. It can be seen as beguiling or ludicrous -- or even both. For an interpretive critic such as myself, it's a challenge.

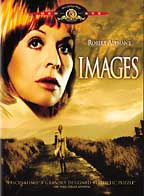

It reminds me of Robert Altman's Images (1972), which could take several viewings to fully decipher. After reflection Wild Grass may not be the same as you first considered it. It's quicksilver.

As in Images, Wild Grass is replete with images that may be imaginary, absurd, irrational, contrived, or actual. They shift and falter, and spin deception.

The plot of Wild Grass is simple. Marguerite Muir (Sabine Azema), after almost obsessively shopping for shoes, has her purse stolen in a crowded walkway. Left without money, she has to go back to the store and return the shoes.

Georges Palet (Andre Dussollier) finds her wallet beside one of his car's tires in a parking garage. He hesitantly decides to go to a police station and give the wallet to a policeman, who returns it to Marguerite.

Marguerite phones Georges to thank him, but this initiates his stalking her, which includes his slashing the four tires on her car. This act seems to end his contact with her.

Eventually she rekindles the warped relationship, which evolves into an obsessive enigma. It ends in a fateful conclusion.

If a viewer depends on the wayward plot in Wild Grass, he or she almost certainly will be disappointed. Wild Grass is more a movie of emotion than of plot, and the emotion is more the director's than the characters.' It's the emotion of a filmmaker -- the emotion of a creator.

Like Cathryn in Images, Georges has a secret. He is stymied by it. Is it actual or imaginary? Was he a killer, a rapist, a shop lifter? What happened in the past that haunts him? Or is it his fantasy?

One might even interpret that it's all in his mind. One might make a shaky case that the repetition of images (the bright yellow bag and red wallet) is a product of his mind. His anxiety caused by two passing girls in the garage may be his fitful imagination at work.

His imagination may suggest that the robber could be his son, that his wife (Anne Consigny) looks more like a daughter than his wife.

He has two contrasting images of Marguerite -- one bland, the other a smiling aviatrix. She's a dentist and a flyer. He fights impulse, and gives in to impulse. His world is one of fortuitous circumstance.

It is a world of greenery growing through cracks in the cement, and visions of flight. Georges loves planes and in a crucial scene goes to a movie theater to a film he loved as a boy -- The Bridges at Toko-Ri (1954). But it no longer does anything for him. He seeks new bridges.

In some ways Resnais may be paying homage to fellow auteurist, the late Francois Truffaut, especially his classic Jules and Jim (1962). As in Jules and Jim, Wild Grass has voice-over narration, a triangle -- Georges, Marguerite, and her friend Josepha (Emmanuelle Devos) --, and a fateful, absurd ending. Resnais, as was his legendary colleague, is a masterly stylist.

Resnais has a pallet (Georges Palet) of vivid colors -- the yellow handbag, blue paint running down a wall, and red. Bright red gives the movie its vivacity -- a red apron, a bright dress, a theater's aura, a covering on a boy, a red robe, a red jacket, red lights on a car, a lamp shade, a wife's coat. Red splashes of life.

The cast is forceful. 64-year old Dussollier portrays Georges, who supposedly is in his 50s. Sabine Azema [who in actuality lives with Resnais] portrays the wayward dentist Marguerite with frizzy red/orange hair.

Wild Grass is adapted by Alex Ravel and Laurent Herbiet from a novel by Christian Gailly.

But whatever its sources, Wild Grass is the vision of Alain Resnais. He suggests that anything can happen in movies.

Or in our imaginations.