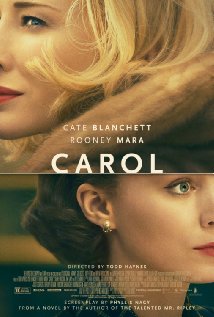

Carol (2015)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on November 27, 2015 @ tonymacklin.net.

Carol is a melodramatic dream. Credible and compelling.

It's a transcendent work of art.

Carol probably shouldn't work. Many will be bored, some offended, and others delighted. If you can get on its wavelength, it may sweep you off your seat. If you don't, you may bolt early from your seat and out the door. But if you let it work, it may work wonders.

Carol - adapted from the novel The Price of Salt by Patricia Highsmith, published in 1952 - is the story of a romance between two women. They don't use the "L" word - actually, they do, "love."

In 1951 Therese Belivet (Rooney Mara) first spies Carol Aird (Cate Blanchett) in a department store in New York City. The young, impressionable Therese is working behind a counter, and the older, impressive Carol is shopping for a toy for Christmas for her 4-year old daughter. Therese is mesmerized by the tall, regal woman in a fur coat. Carol, blonde and almost haughty, is remote and distant but friendly. She is a commanding vision.

Therese helps Carol pick out a toy train for her daughter, and Carol exits. But she leaves her gloves behind on the counter. Therese sends the gloves to Carol at her grand home in the suburbs. Although the two women are very different in age and bearing, they slowly become friends. The relationship at first is tentative and uncertain, although each seems to harbor the desire for greater involvement.

Carol's marriage to Harge (Kyle Chandler) is coming apart, and she and Therese drive west to Chicago and beyond. Their relationship goes beyond.

But Carol faces the loss of her daughter whom she loves, because Harge brings a suit with a moral clause against her.

The two women are separated. In desperation, they both try to face their fates and cope with their lives.

Carol is a showcase for two brilliant performances. It's hard to imagine Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara being better. If their chemistry doesn't seem what one expects, it's because it is quiet and fitful. At the beginning Cate Blanchett may seem to be playing a role, but it's because her character Carol is playing a role. As the film develops, her humanity is shaken and her fervor increases.

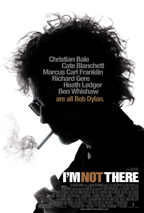

Haynes knows Blanchett well, since she was the best incarnation of Bob Dylan in his I'm Not There (2007).

It takes a moment to realize that Rooney Mara has changed from being Lisbeth Salander and become Millie Perkins. And at times Mara also has an uncanny resemblance to Audrey Hepburn. Therese is a character of furtive glances and long looks.

Both actresses inhabit characters who change, and subtlety that grows. They are wonderful.

Todd Haynes directs with masterly creativity. Carol has layers of meaning in its images.

Carol has the feel of some melodramas and romances of the 1950s. But Haynes brings a 21st century perception to the material. The main sex scene between the two women is not just a blur and motion. It's explicit, and vividly shows them in the intimate throes of passion. Any sexual passion in the movies of the 1950s was off screen.

It's remarkable to think that in 1953 The Moon is Blue, an innocuous comedy, was refused the Production Code's seal of approval and was condemned by the Legion of Decency. One of the complaints was that The Moon is Blue used the word...wait for it, "virgin."

One of the states that banned that film was Ohio, and in 2015 Cincinnati is the setting that the film Carol uses as a stand-in for New York. How times have changed.

A prevailing motif in Carol is hands. It's a ballet of hands - grasping, clutching, pointing, feeling. In scene after scene, the film focuses on hands and their movements and positions, and sees meaning in them. If you recognize this, you know you're getting on the film's wavelengths.

There are shots of the touching of a shoulder, the lifting of a glass, a hand lifting the arm of a record player, a hand taking a 78 Columbia record from a sleeve, hands with cigarettes in them and plumes off smoke billowing up.There's a hand holding a pen, a child crayoning, a hand with a bracelet on its wrist, a hand fumbling in a pocketbook.

Carol strokes her daughter's hair with a hand, she clutches her hand. She holds tightly onto her daughter, onto Therese, and onto her friend Abby (Surah Paulson). Carol throws her hands in front of her face as Therese takes her photograph. And Carol sits across from Therese with her hands folded under her chin. Carol pushes the disconnect button on the phone with a finger on her hand. Hands control and lose control.

On the television is a scene from Sunset Boulevard (1950) with William Holden in a tux. That film ends with Norma Desmond's hands reaching out. But Haynes is too subtle to use that.

Carol is an evocative experience. The cinematography of Edward Lachman is lush. The soundtrack adds to the spell. Carter Burwell's score is all strings and piano.

And standards from the 1950s abound. In the car as the two women travel, "You Belong to Me" plays on the car radio. Perry Como sings "Silver Bells" as they drive through snowy terrain. And Patti Page's "Why Don't You Believe Me?" and Jo Stafford's "No Other Love" capture alienated enchantment.

Haynes refers to the times in other ways. In one scene, on the radio in the background we hear a report about the death of Hank Williams. We also hear the New Year's celebration from Times Square.

The most satiric scene is around a table after Carol has parted from Therese, and Carol is trying to regain her equilibrium. She sits at dinner with her estranged husband and his parents. The mother-in-law prattles superiorly about money and Carol's' "doctor" - a psychotherapist. Eisenhower is giving a speech on television. It is a harrowing glimpse into Eisenhower America.

Phyllis Nagy's screenplay basically is true to Patricia Highsmith's book.

If the film had been made in the 1950s, it would end in suicide. But the positive ending in the book is the same in the film in 2015.

The novel is provocative but not much on description. Haynes has taken a spare novel and deftly made it into a vivid film. He has made an offbeat film that is accessible to more audiences. Highsmith, who generally had the reputation of being an unpleasant person, might think the film is too audience-friendly.

There's one possible exception. One of the key lines used twice in both book and film is problematic in the movie. Unfortunately it's not as clear as it could be.

The line "flung out of space" is odd, but crucial in both the book and the film. But in the film it lacks enunciation. It winds up being a "what did she say?" line.

The first time it is used is when Carol says to Therese, "What a strange girl you are."

"Why?"

"Flung out of space."

The second time it is used, Carol says, "My angel." Then she adds, "Flung out of space."

The movie Carol is, in the words of Highsmith, "flung out of space."

Whether it's caught or not is up to the audience.