Last Hurrahs

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on June 1, 2006 @ FYLMZ.com.

The release of 81-year old Robert Altman's A Prairie Home Companion raises the issue of a director's farewell. Although it may not be Altman's last movie, the end of his career is approaching.

A Prairie Home Companion would make an incomplete finale. Yes, it's a movie about endings -- the closing of a theater, the end of a popular radio show, the death of an old man, progress paving over tradition.

But A Prairie Home Companion is more a Garrison Keillor movie than a Robert Altman film. One hoped for a big party with a lot of the Altman troupe cavorting in bit parts. which would bring back the warm glow of his past creativity.

Instead only Lily Tomlin was invited (to play one of the country-singing Johnson Sisters with Merle Streep). Where was Shelley Duvall? Elliott Gould, Rene Auberjonois, Sally Kellerman, and Keith Carradine? Paul Newman, Tim Robbins, and Michael Murphy? Jennifer Jason Leigh?

Maybe I'm being selfish for Altman, but I want to see the old guard again. Instead Garrison Keillor took center stage, and Altman slipped back into the wings.

Keillor is the focus of the movie. His mellifluous voice and personality were made for radio. In the flesh his shambling, stoic image dulls the screen.

Like Keillor, Altman was born in the midwest. He made a movie honoring his roots in Kansas City (1995), but Altman's sensibility is not midwestern. It is otherwordly; it is humanistic iconoclasm. Altman made movies set in alien territories, but they were also always set in his own heart and mind. They were always Altman films.

With A Prairie Home Companion Altman lets himself be subservient to Keillor. Altman told the LA Times, "I have to be sure he is in charge."

Keillor said, "This has been my ambition for years to write for a dramatic medium. Because I'm no good at it, and one aspires to do what one cannot do."

Great, this is just what Altman needs at this point -- someone who can't write for a dramatic medium!

A misbegotten decision that Altman went along with was Keillor's hoary suggestion of an angel in a white trench coat. Altman used an angel to good effect in Brewster McCloud, but in A Prairie Home Companion, it seems just a tired device. She (Virginia Madsen) flits around like a carhop waitress waiting to take an order.

A more generous sort than Keillor -- even if Altman had resisted -- would have invited Altman's old friends to the party. Their absence leaves a void. It diminishes Altman's presence.

A Prairie Home Companion has one bit of terrific casting. L.Q. Jones plays country singer Chuck Akers. Jones who turns 79 this year was a great character actor. He was in five Sam Peckinpah westerns. He was the yang to Strother Martin's yin. Ironically, Peckinpah and Altman were born in the same year 1925, but Altman has outlived him by 21 years. Peckinpah's last film was the bedraggled The Osterman Weekend (1983).

One bit of casting in A Prairie Home Companion that didn't reach fruition is that Willie Nelson and Lyle Lovett originally were cast as the two cowboys, but left the cast when the film was delayed. They were replaced by Woody Harrelson and John C. Reilly, but Willie's iconography can't be replaced.

A Prairie Home Companion makes one think of other directors and their last movies. Maybe Altman will make several more, but Howard Hawks and John Ford were not allowed to make a movie the last seven years of their lives. Hawks died at 81, and Ford at 78. Another irony is that the man's man director Ford's last movie was Seven Women.

I visited Alfred Hitchcock on the set on his last movie The Family Plot (1976). He still was vital then, but he faded and did not make another film the last four years of his life. Like Hawks, Hitch never won an Academy Award for his directing. Although Rebecca won an Oscar for Best Picture (1940), John Ford won the Best Director award for The Grapes of Wrath. The only Oscar Hawks and Hitch received was an honorary one. Altman also has received an honorary Oscar.

The Family Plot is full of playful references to Hitch's past films. Hitchcock said, "Style is self-plagiarism," and the old rascal plagarized himself with aplomb. Maybe it is a negligible movie, but The Family Plot is pure Hitch. He even has Bates on a street sign. And the number of carats in the diamond the cast pursues is the same as Hitchcock movies. Now, that's the way to go out!

Another director who went out with great personal style is John Huston. His final movie The Dead (1987), from a story by Irish master James Joyce, was a labor of love. Hooked up to an oxygen machine, Huston devoted himself to his personal art. The Dead was not a popular film, but it honors both the director and the medium.

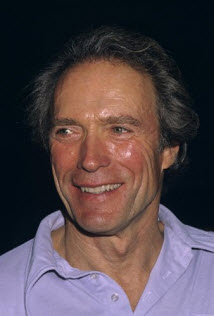

Another director on the back nine, although he may be active for another twenty years, is Clint Eastwood who was 76 years of age on May 31. His birthday was a week after his pal and collaborator production designer Henry Bumstead died at the age of 91. Bumstead and Eastwood worked on 13 films together.

Whatever the future holds, Eastwood has already made his elegiac exit. Near the end of Million Dollar Baby in the penultimate sequence, Eastwood walks down a dark corridor in the hospital and out the door. It is an exquisite moment. Frozen in time.

That moment eluded Hawks, Ford, and Peckinpah. Hitch and Huston had it

Altman deserves it. But A Prairie Home Companion isn't it.