Hereafter (2010)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on October 20, 2010 @ tonymacklin.net.

Alfred Hitchcock should not have made musicals. He didn't.

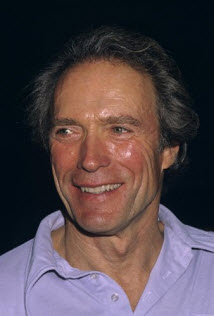

Probably Clint Eastwood should not make sentimentalized, epical films about wish fulfillment. But there's Hereafter.

It's a film that might make Clint's mentor the late Don Siegel look away.

With Hereafter, Eastwood may have reached the point I was afraid he'd reach ten years ago -- moribund filmmaking.

I've been a cautious devotee of Clint for years. I taught a university course on him. [Some alumni were horrified, but I think my choice has been well-validated.]

I had a lengthy interview with Clint at the time of Million Dollar Baby (2004). I've thought of myself as that movie's lucky charm, since the three people I interviewed -- Clint, Hillary Swank, and Morgan Freeman -- all won Oscars for their contributions to that movie.

Although I originally thought the simple entertainment, Space Cowboys (2000) would make an adequate farewell by Clint, he had an entire decade of vital creativity ahead of him. Several of his films were original, and some were important.

Gran Torino (2008) might have bid a fond farewell.

Mystic River (2003) was brilliant, but what followed were significant culturally. Flags of Our Fathers (2006) and Letters from Iwo Jima (2006) were brave looks into the past.

Clint's strength has been looking back not forward. Even Changeling (2008) worked because of Clint's style, which was both simple, evocative, and provocative. Although the material may not have seemed conducive to his touch, it was.

Clint escaped potential pitfalls with his faculties intact.

He was not so fortunate last year. His production of Invictus (2009) was bloodless and surprisingly uninvolving, although the topic of Nelson Mandela seemed almost sure-fire.

Given the disappointment of Invictus, I went to Hereafter with trepidation. Clint blew it away with his opening segment of a smashing, raging tsunami in Indonesia. It's a terrific sequence.

Unfortunately it's by far the best scene in Hereafter. You can leave the theater after the first fifteen minutes, without missing anything else memorable. The opening sequence is reason enough to see Hereafter, but prepare to lose your original enthusiasm almost immediately.

After the opening, much of Hereafter seems stuck. Clint learned from Siegel how to be terse and direct. But Hereafter is logy and obtuse.

Hereafter is a story focusing on a trio of characters. Marie LeLay (Belgian actress Cecile de France) has a near-death experience in the lethal tsunami, which changes her life. She is hostess for a political program on French television, but she is unable to function as she once did.

The second main character is George Lonegan (Matt Damon), a psychic in San Francisco, who runs away from fame and the human damage he sees. He sees his gift as a curse.

The third pivotal character is a young boy in London. The youth Marcus (played by George and Frankie McLaren), is overwhelmed by a death that obsesses him.

All three main characters are adrift, seeking some human resolution. Eventually they come together in their quest.

I tried to figure out why Clint made Hereafter. The easy answer is he's 80 years old, but that doesn't jibe with his vision. A constant theme in Clint's work -- both as actor and director -- is redemption. But usually it's not writ in capital letters.

Ordinarily there's a wry, hard-boiled intelligence in Clint's movies, not the soft-boiled emotion that nags in Hereafter.

Hereafter is not a movie that Clint would have made at the beginning of the decade. Hereafter may be a movie for 2010, when intelligence is in regression. The movie probably doesn't have legs into the future, because its mind is so narrow. Hereafter is without mystery.

Clint's best movies go back into the past to ferret out truth. He seems out of his natural depth in the future.

Can Hereafter be seen as a metaphor for a popular actor/director? Doubtful.

Much of Hereafter, in some ways, seems to be a movie made by a novice, with overlong shots and plodding exposition. The scenes in the culinary school seem like an acting exercise.

The acting is mostly serviceable. Matt Damon holds on for dear life as the psychic; he does what he can with a leaden role. The two lads who play Marcus are affecting. Cecile de France struggles with her sodden role as Marie -- often just limited to staring into space. Bryce Dallas Howard uses coyness as a cudgel as a possible romantic interest for George.

I never thought I'd say this, but the actor who has the most personality is a chef/teacher played by Steve Schirripa.

The superficial screenplay is by Peter Morgan.

I know filmmakers love dualities, contrasting pairs, doppelgangers, two sides of existence. I realize too much can be made of it, but it can be an interesting subtext. Dualities worked really well in conveying meaning in The Social Network (2010).

But in Hereafter, dualities are not as effective. There are twins, and George and his brother Billy (Jay Mohr), two teddy bears, and two publishers -- English and American, affairs with two tv hostesses, two adopted boys, two social workers, two rescuers, pairs at culinary school -- each pair has a masked partner, and on and on. But they seem Hereafter-thoughts.

I hope I'm wrong, but Hereafter seems like incontinent filmmaking.