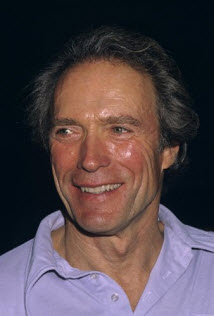

Clint Eastwood's Spiritual Journey

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on December 20, 2008 @ tonymacklin.net.

Clint Eastwood makes religious movies.

One's first reaction might be to scoff at that statement. Eastwood is thought conventionally to be an action star who makes violent movies, with an occasional romantic interlude -- such as The Bridges of Madison County -- or a shaky character study -- such as White Hunter Black Heart -- to give his image some breadth. But his blood and butter is violence.

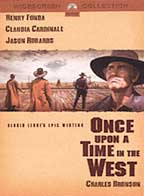

When one thinks of Eastwood, it's the action operas that spring to mind: Dirty Harry, the Sergio Leone Spaghetti Westerns, Where Eagles Dare, The Outlaw Josey Wales, and Unforgiven.

But more and more, recently Clint Eastwood is being considered an artist. Mystic River, which Eastwood directed but did not star in, has received rave reviews as a special film of depth and quality. Like Alfred Hitchcock, it has taken Clint Eastwood a long time to be treated seriously. The action genres that Eastwood assays are as deceptive as the suspense genres that were such a part of the Hitchcock oeuvre. As in the films of Hitchcock, Eastwood's films have themes that are allegorical, philosophical, and religious. This is not to say that Eastwood's films are dogmatic, but they do deal with spiritual issues, such as good and evil, the effects of materialism, crises of faith, and what it means to be human. At present there is a critical rush to give Eastwood his due, but it's still haphazard -- the religious level has seldom if ever been plumbed.

Two of the primary themes in Clint Eastwood's movies are redemption and the cost of vengeance. And often the primary figure that provides that redemption is the well-used myth of the Christ figure. Sometimes the Eastwood character is the Christ figure, sometimes it's the villain who brings the Eastwood character redemption, or the leading character's vengeance provides another character with redemption.

It's not unusual to find the Christ figure in movies: directors such as Arthur Penn, Marty Scorsese, Hitchcock, Kubrick, Peckinpah, et al. have employed the figure with finesse.

Early in his career Eastwood was put into this equation. Director Sergio Leone gave Eastwood his first starring role in A Fistful of Dollars (1964), and together they made a moral tale, at times with tongue in cheek. Usually one remembers Clint's cigar and flinty eyes, not the spiritual heart. In the movie's opening, Clint -- "The Man with No Name" -- rides into town on a mule and ultimately saves Julio, Mary, and the child. At one point a character looks at him and says, "Jesus." It seems to have stuck.

Leone embarked on another moral tale in The Good the Bad and the Ugly (1966) with Clint and two thieves. The Ugly was played by El Allah, who has a cameo in Mystic River; Clint doesn't forget his past.

The movie that perhaps made Clint the poster boy for violence was Don Siegel's Dirty Harry (1971). Pauline Kael said the movie was fascist. But beneath the guns and gore was a strong moral sense. Harry was anti-Establishment (when's the last time we heard that term?) because the Establishment had been corrupted, and the movie revealed the declining values in America. In Dirty Harry, Siegel also brilliantly used the doppelganger: Scorpio, the vicious killer, and Harry Callahan were two sides of one being. Like Scorpio, Harry too is a voyeur, sometimes a bigot, and an outsider.

Both men have Christ references. Harry is beaten beneath a huge cross in a park, and behind the wounded Scorpio on a football field is a cross of lime. Harry gets a wound in his side. The Christ allusions are as ironic as the distorted cross, peace symbol buckle Scorpio wears. In his quest for redemption, Harry finally kills his double. But what is left? He is alone, walking away. Badgeless in Gaza?

In his first directoral stint with the help of Siegel, Eastwood both starred in and directed Play Misty for Me (1971) and continued the quest for redemption. His character Dave is redeemed by the villainess Evelyn, who plummets to her death with arms outstretched. Eve falls. lf one is dubious about the Christ reference, the Eve reference is less deniable.

Another film in which the villain has a Christ dimension is In the Line of Fire (1993). It has a smart script by Jeff Maguire, which is among the best scripts for Eastwood's movies along with the Finks' Dirty Harry, David People's Unforgiven, and Brian Helgeland's screenplay of Dennis Lehane's novel Mystic River.

ln the Line of Fire is about Secret Agent Frank In (Eastwood) who was assigned to protect John Kennedy and has never gotten over that he was unable to save the President from being assassinated. But he gets a second chance when another President is threatened by an assassin. Looking down a list at a campaign function, Frank recognizes the alias of the killer and reads, "Carney, James. Jesus!" Maybe JC is just a Jackie Chan figure, but it is unlikely. The climax is when Frank wrestles with the killer in a glass-enclosed elevator. The killer even says to Frank, "I redeemed your pathetic, shitty life." He lets go of Frank's hand and falls -- like Evelyn in Play Misty for Me -- with arms out, to his death and Frank's redemption.

In The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), after the death of his wife, Wales (Eastwood), like a crucified farmer about to seek revenge, leans on a cross by the grave of his wife, before becoming an avenger.

Sometimes the Avenger in Eastwood's films pays an ultimate price. In Unforgiven (1992), for which Eastwood won an Oscar for best director, the Schofield Kid is saved from the path of violence, but Will Munny (Eastwood) wallows in it. As Little Bill says to him, "I'll see you in hell." At the end after a deluge of rain and a deluge of killing, Munny visits his wife Claudia's grave. The narrator says of Munny's fate, "Some said to San Francisco where it was rumored he prospered in dry goods." Claudia should have redeemed him, but perhaps he lost his soul , to killing and dry goods. Is he revenged but ultimately unforgiven?

In Mystic River -- a reservoir of Eastwood's themes -- as in Unforgiven, the major character Jimmy Marcum (Sean Penn) gets his vengeance but is damned in the process. Violence -- actually wrong-headed violence -- prevails. Mix in a parade at the end, and you have some traditional Americana.

Jimmy, a vengeful murderer, walks away from his boyhood friend Sean, with arms out. For Jimmy, with a cross tattooed on his back, vengeance will out, whatever the cost. But because of his involvement with Jimmy and his past, Sean is redeemed. Mother and child and husband are saved.

From A Fistful of Dollars to Mystic River, religion flows through the movies of Clint Eastwood. It is deceptive and allegorical, but it is continuous. It is a very human journey.