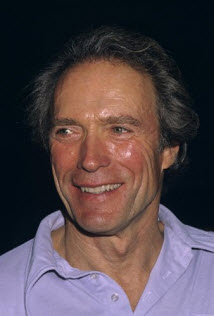

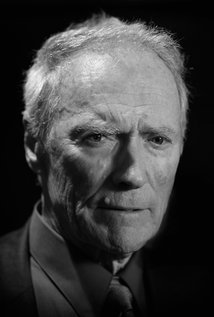

Clint in the Classroom

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on December 21, 2004 @ University of Dayton Quarterly.

A college course on Clint Eastwood?

I would have cringed at the idea a few months ago. In an English department?

Shakespeare, Milton, and... Clint? "What has happened to education?" I would have mused disparagingly, if not scornfully.

But after three months in the classroom with Clint, I have been enlightened. Clint Eastwood's films have more consistency, depth, and quality than I ever imagined. Clint Eastwood is an artist.

What brought me to this strange moment of truth?

The last couple of years I've been considering writing a book about a film figure as the capstone of my career. I considered doing a book about director Bob Rafelson; in fact, I had a publisher interested, but nobody knows Rafelson even though he has directed Jack Nicholson more often than any other director has. The Rafelson/Nicholson version of The Postman Always Rings Twice has worked very well in class in awakening students' perceptions, and Five Easy Pieces is a milestone, but The King of Marvin Gardens -- though one of my personal favorites -- doesn't connect with many students. And I got tired of explaining who Rafelson is and getting a bland look from people in response to my planned project.

I sent to the publisher another list of directors whom I was interested in writing a book about and included Eastwood.

Now when I told people I was considering writing a book on Clint Eastwood, nearly everyone's eyes sparkled with anticipation. Everybody knows Clint.

I don't want to sound callow, but at this point in my career I'm not much interested in fighting the good flight -- that war is endless. Since publishing is so much name recognition, I could provide the quality; Clint could provide the name recognition.

And of course the publisher was interested. The editor of the series I was considering was sanguine, but the publisher though positive was in the throes of reorganization. They would contact me soon. (The contract is still pending.)

With the Eastwood project in mind, I spent the summer watching Rawhide reruns twice a day on the FX channel on cable. I saw a young Clint romping and crooning all summer.

This fall I had planned a course on the theme of alienation in film using Citizen Kane and other works, but since I was to write a book on Eastwood's films I decided to change the course to Eastwood. It was a self-indulgent moment, but since I believe the prof makes the course, I could do anything. Eastwood? Why not?

I'd "sold" Moby Dick and The Waste Land in class; I certainly should be able to "sell" Clint. And some of the students already had an affinity for the subject matter -- much more affinity than to prose or poetry.

So I put together a syllabus on Eastwood; A Fistful of Dollars (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly didn't fit the time constraints), Where Eagles Dare, Dirty Harry (I had taught this before), The Beguiled (I used this when I was a visiting prof in the film department at the University of California at Santa Barbara), The Outlaw Josey Wales, TV episodes from Rawhide, Play Misty for Me, The Eiger Sanction, In the Line of Fire (I'd used this before), and Unforgiven.

Since the course ostensibly was Literature and Film, it had to have literature. I selected three books: Alastair MacLean's Where Eagles Dare, Forrest Carter's Gone to Texas (Josey Wales), and Trevanian's The Eiger Sanction. Before the course I didn't even know there was a Carter or Trevanian.

On the first day of class I gave out the syllabus and rendered an apologia for the change in subject matter. I could see the looks of doubt in the eyes of two English majors (a blond and a bohemian). After class I offered them both a tutorial on material from the original course, but they tentatively returned to the Eastwood course. We were reluctantly ready.

A Fistful of Dollars was the first surprise. I knew I could emphasize the music of Ennio Morricone (Dan Savio) and talk about director Sergio Leone's personal film poetry, but the film had more to explore and interpret. It had symbols of death, Joseph and his wife, and a hero who rode into town on a mule. It was edgier than I first realized. And I was able to trot out my mulish interpretation of religious symbolism. With Where Eagles Dare we contrasted the styles of the book and film. I had used the doppelganger, the double theme, in Dirty Harry to good effect in a previous course. We compared and contrasted Harry and Scorpio and focused on director Don Siegel's vision of America's values.

We followed with the film Siegel has said was his favorite, The Beguiled. This was my trump card; with it I was going to trump the conventional image of Eastwood. It is the first Eastwood film that really shatters preconceptions. The unsympathetic Eastwood character dies an ignominious death. Very few people have seen The Beguiled; none of my students had. It was a coup.

We had explored myth in A Fistful of Dollars, adventure in Where Eagles Dare, the doppelganger and Siegel's social criticism in Dirty Harry, and iconoclasm in The Beguiled.

Now we were ready for Eastwood as director. We saw The Outlaw Josey Wales, which Eastwood directed, and read Carter's Gone to Texas and analyzed how literature had been translated into film. And with The Outlaw Josey Wales, redemption of Eastwood's characters became a man or theme in the course.

At this point, the course had become formidable. It got its soul with a film I added at the last minute. I was looking through my collection of tapes trying to decide which episodes of Rawhide I would use, when I came across Don't Pave Main Street. This is a documentary about Carmel, California, narrated by Eastwood, who served as Carmel's mayor from 1986-88.

For me this was the central film in the course. As he stood before the Pacific Ocean, walked around Carmel, and spoke his narration about the soul and spirit of the town and about Lincoln Steffens, Jack London, and Robinson Jeffers, Eastwood evoked a sense of place and vulnerable human spirit. It totally humanized him.

The next film in the course, the first film Eastwood directed, Play Misty for Me, was made in Carmel, and Carmel served as an evocative presence. We had focused particularly on the theme of redemption in The Outlaw Josey Wales, and Play Misty for Me gave us another film with that defining theme. The death of a psychotic woman redeemed Clint's character.

Our next film and book was The Eiger Sanction. The students found the Trevanian book a bit provocative, but the script of the film, credited to three writers, is dismal. The dialogue is appalling. But the film does have its value in the way that Eastwood photographs Monument Valley. If Carmel was a special presence in Play Misty for Me, Monument Valley gives The Eiger Sanction its resonance. Clint leaves personal footprints along side Ford's and Leone's.

With In the Line of Fire we were able to contrast the shoddy script of The Eager Sanction with the effective script by Jeff Maguire. And all the themes we had considered were clicking: redemption, doppelganger, search for identity. Into this equation was Clint's own persona, the aging professional. One of the elements we had often noticed was Clint's awareness, and his directors' awareness, of his image -- sometimes self-deprecating, a mixture of the heroic, comic, and the vulnerable. A glower, a wink, and a grimace. And that soft raspy voice.

Maguire, the director Wolfgang Peterson, and Eastwood use this to great advantage In the Line of Fire. And, for one of the few times Eastwood is paired with a major male acting talent in John Malkovich who himself has star power. Eastwood has had a few major actors in his films -- Burton effectively coasted through Where Eagles Dare -- but usually his adversaries, such as Andy Robinson in Dirty Harry, do not have star power. In his later films Unforgiven and In the Line of Fire, Eastwood shared his screen with other major male actors and created a potent chemistry.

With In the Line of Fire I was even able to work in my English teacher peculiarities such as the Malkovich character as the Christ figure. And, Eastwood's own reality was emphasized as the media's flashbulbs kept the lovers apart. Actuality, anyone?

Unforgiven (its not "The Unforgiven," Charlie Rose. Ask the question and shut up, Charlie) was the piece de resistance of the course, as it seems to be of Eastwood's career. It won the Oscar as best picture of the year, and Eastwood received the Academy Award as the best director of 1992.

But I was a little uneasy. I admired Peckinpah's and Leone's and Ford's elegies for the Old West and perhaps the western itself. I love romance, and I like passion. i made me uncomfortable. But there was a whole lot to work with in Unforgiven. Was there redemption? Of whom? There was the doppelganger with William Munny and Little Bill. There was satire of the media. There were the parallels between Munny and Clint. And there was a strong metaphor with American society. William Munny -- the man of frontier violence -- is reported at the end of the film to be "prosperous in dry goods in San Francisco." But has he lost his soul?

The last class was an enthusiastic debate.

Afterward I considered my relationship with the subject I realized that my 35-year career as a teacher equated to his as a film creator. There were other ironic parallels. Both my mother and daughter were born on May 31. Guess who else was born on May 31? Perhaps my kinship with Eastwood was fated.

And the course? Basically we discovered that Clint Eastwood and his films are worthy subjects for a college course. Clint's image is deceptive. He doesn't reveal himself easily. He is taciturn, minimalist, and succinct. Like Hemingway, his persona obscures the subtleties of his work. But they are there and can be revealed.

I rummaged around to find a literary excerpt that I thought might be apt. In Shakespeare's Henry IV, part 1, Prince Hal says of himself:

"Yet herein will I imitate the

sun,

who doth permit the base contagious clouds

to smother up

his beauty from the world,

That when he please again to be

himself

Being wanted, he may be more won'red at"

These lines apply to Clint and his image.

In the course of the Films of Clint Eastwood, we explored Eastwood's persona and the style of his films. We were able to interpret themes and the many layers of the vision in his films. His work is truly personal.

The course was a revelation to many of us. And maybe that's what education is all about.