Invictus (2009)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on December 7, 2009 @ tonymacklin.net.

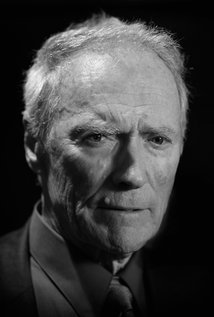

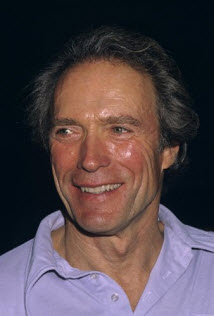

Make no mistake about it, I'm a fan of Clint Eastwood.

Eventually he will be my model for aging gracefully with his creative faculties intact and flourishing. If I ever reach the age of 79 [Clint's age -- born May 31, 1930], I hope I have just a little of Clint's aplomb.

One of the best interviews I ever had was the hour and 45 minutes I spent sitting next to and talking with Clint. It was prior to the release of Million Dollar Baby (2004). I also interviewed Morgan Freeman and Hillary Swank. All three won Academy Awards for Million Dollar Baby, so I considered myself a lucky talisman for them and the movie.

I had assumed that Clint's career might end with Space Cowboys (2000) -- a geriatric film about geriatric heroes. It appeared as though Space Cowboys might be Clint's apt farewell before he sauntered into the sunset.

Hardly.

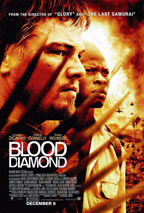

Clint had a startling decade before him. After Blood Work (2002), Clint directed the powerful Mystic River (2003).

Then Clint went on a mission creating films that were works of art with a humanistic point of view. Clint's movies were out to influence society's attitudes and perhaps to change them.

Million Dollar Baby was about a female boxer and dealt with euthanasia. Then Clint made two movies about World War II -- Flags of Our Fathers (2006) and Letters from Iwo Jima (2006). The latter was told from a Japanese point of view. What would John Wayne have thought about that?

Last year Clint took on the justice system (Changeling) and also racial intolerance (Gran Torino).

Now he's at it again with a movie about Nelson Mandela and his quest to unite a nation. Invictus is his latest movie promoting a cause for humanity's betterment.

If only Invictus were a better picture.

Invictus is like a professor emeritus (Morgan Freeman or Clint) reading from dusty, scrawled notes from a distant lectern.

The lecture has no fervor. It has no immediacy. We listen because we admire the prof, but the history lesson seems almost abstract and a little dull.

The title of the film Invictus is from a poem by British writer William Ernest Henley, a poem which Mandela used as a source of inspiration while he was imprisoned for 27 years.

In high school I had to memorize the poem -- I can still recall it. Invictus is a pedestrian, rhyming poem that a high school boy could remember.

Freeman does give it an effective, sensitive reading in the movie, but remember that mellifluous voice can sell forgiveness or hawk Visa. Mandela is a great man; Henley's poem is not great verse.

For a long time Freeman had wanted to portray Mandela, but he needed a suitable property -- not just another telling of the basic tale. John Carlin's book Playing the Enemy: Nelson Mandela and the Game that Made a Nation provided him an appropriate opportunity.

It's hard to imagine that the tame Invictus was directed by the same man who directed the very raw Unforgiven (1992). Unforgiven had violence, passion, and profound impact.

Invictus is a film that avoids any harsh reality, which is a hard thing to do in South Africa.

Invictus is the story of how Nelson Mandela, freed from incarceration and elected president of the Republic of South Africa, tried to unite his nation. Mandela tried to use the national rugby team to unite the country behind the team's quest for the World Cup.

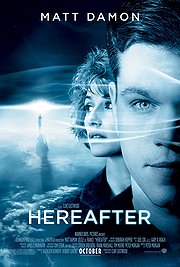

Mandela enlists Francois Pienaar (blond and buffed Matt Damon), the team's captain, in his cause.

One might blame the movie's diffidence on Clint's age, but maybe it's just a faulty creative choice. Clint directs with kid gloves.

If you like to see endless shots of cheering crowds, Invictus may be for you. It's as though Clint napped while editing, and let the film roll.

The best thing about Invictus is the cinematography by Tom Stern. But when Stern's lighting is the most dramatic thing in Invictus, you know it may be a little light.

There is little action except on the rugby field, but scrums don't move much. The only tension is provided by a van delivering newspapers. There are lots of shots of security men watching and waiting for something to happen. Nothing does.

Characterization, except for the blissful Mandela, is skimpy. Francois appears in a few scenes with his wife and parents, but there's no substance to the relationships.

Invictus has little, if any, conflict. The bigotry which seized South Africa is diluted to a few lines of dialogue and a few glances. The most emphatic moment of bigotry is when a taxi driver chases a black boy away from his vehicle. Don't worry, they wind up hugging each other.

Invictus is caught in a rugby scrum between Clint's good intentions and dull execution. I love the game, but am disappointed in the match.

Invictus is more wishful than authentic.

It's like Dirty Harry now is saying, "Make my daydream."