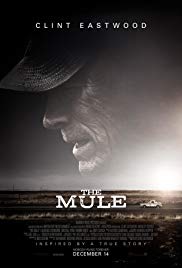

The Mule (2018)

Content by Tony Macklin. Originally published on December 19, 2018 @ tonymacklin.net.

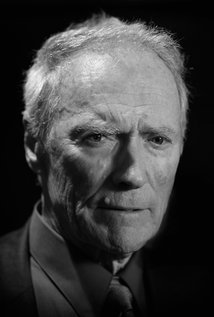

Clint can be proud.

The Mule is a film to take seriously. It belongs in Clint Eastwood's legacy.

The Mule is the story - based on Sam Dolnick's article in The New York Times Magazine - about an old man, who becomes a drug mule for a powerful Mexican cartel.

Screenwriter Nick Schenk changes Leo Sharp's name to Earl Stone, and fashions it to Clint's persona. And Clint runs with it - not so much runs, as dances to his own beat.

Unlike Robert Redford - six years Clint's junior - who coasted through this year's negligible and forgettable The Old Man & the Gun, Clint gives a committed performance. He takes risks. He and his film have a briskness. Although occasionally gnarly, The Mule has legs.

It may take a while to adjust to the image of the 88-year old actor on screen. At first he seems fragile - almost frail. This is not Harry Callahan or Rowdy Yates or The Man With No Name.

This is the man with baggy pants.

But as the film evolves, so does Eastwood's performance. One becomes acclimated to Eastwood's ancient Clint, as Eastwood gets acclimated to his ancient character. Leo Sharp becomes Earl Stone becomes Clint Eastwood.

Clint, whose last major screen appearance was in the uninspired Trouble with the Curve (2012), needed a better film as his on-screen finale.

Nick Schenk, who wrote the screenplay for The Mule, also wrote Gran Torino (2008), which was the last real Eastwood film. He directed and starred in it. It was the last film Eastwood appeared both in front of the camera and behind it.

Until now.

Gran Torino is classic Eastwood. The Mule is semi-classic Eastwood.

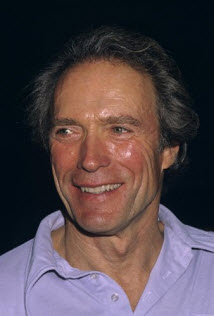

When I met Clint Eastwood, I was surprised by two things. He was gentle, and he was well-read. That gentleness and perceptiveness are two qualities that aren't usually mentioned with Clint. But they affect his acting.

There are those that think Clint can't act or that his acting is one-dimensional. But we know better.

Clint has a combination of different expressions in The Mule. His smile is engaging - gentle but often with a glint in it. He looks harassed and fearful when thugs face him in the woods. He has an angry outburst in a garage. He sings with gusto with Dean Martin, Roger Williams, et al. on the car radio. In another scene as he's driving through the rain, he talks on the phone with his granddaughter and he looks sad and helpless. He is baffled by modern devices, and he treats them with quiet mockery. He looks at his former wife with wistful regret.

Clint's character also is smart and resourceful. He uses Ben Gay and caramel corn to con police.

There are a couple of scenes that strain credibility, but there is humor to leaven them. In both he is with two women. Earl cries, "I need my cardiologist."

Schenk also gives some dialogue that seems to reference movies. To a cop he talks about his dog "Dukey." When I was trying to set up an interview with Clint, I told him I had done an effective review with John Wayne. The aide replied, "Mr. Eastwood hates John Wayne." And later the cop says to Earl that he liked his impression of Jimmy Stewart. Make of it what you will.

Eastwood is surrounded by an able gifted cast. Bradley Cooper, Michael Pena, and Laurence Fishburne are DEA agents. Cooper nicely underplays his part. At a counter in a Waffle House, his character and Earl have a conversation about family that rings true. It is difficult to fathom how much of the film has personal connection to Eastwood's own experiences. But it invites consideration.

The Mule obviously has some personal qualities for Eastwood. He dedicates it after the credits, to "Pierre and Richard." Pierre Rissient was a French cineaste and festival mentor for Eastwood, and critic Richard Schickel wrote a biography of Clint. Schickel died in 2017, and Rissient died in May of this year.

Eastwood's daughter Alison plays Earl's daughter, and Taissa Farminga [Vera's sister] plays Earl's loyal granddaughter. Dianne Wiest does her best with a rather thankless role of Earl's former wife.

The final shot in The Mule also seems meaningful. Clint in the far distance walks off the frame.

I always thought the best coda for Clint Eastwood was the penultimate sequence in Million Dollar Baby (2004) when alone he walked down the hall in a hospital and out the door into the darkness. But Clint has come up with a different coda.

At the public showing of The Mule on a Monday at 3 pm, the theater was much more crowded than usual. After the film ended, most stayed for the credits. The theater usually is empty then. People remained.

It was like they were saying goodbye to an old friend.